I’m hesitant to write this because there is already so much information available at the push of a button. But to begin properly, I need some sense of order and definition—even if only for myself. A good place to start is with a, general understanding of what ADHD actually is. This is what I know about ADHD.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder—ADHD was once a separate diagnosis from ADD which stands for simply Attention Deficit Disorder. One included hyperactivity and one did not. As of presently Doctors and neurologists have merged them into a single disorder under the umbrella term ADHD – with different presentations. My personal belief is that all ADHD people present with hyperactivity, but for some, it’s primarily physical; for others, it’s mental hyperactivity.

I didn’t officially learn about ADHD until I read Driven to Distraction by Ned Hallowell. I had heard the words ADD and ADHD before, but in my mind, ADD was a “hyperactive disorder,” or simply an “I can’t focus” kind of brain.

I thought it was a boy thing.

I thought it was a childhood thing.

I thought it was a can’t-sit-still thing.

I didn’t fit any of those categories.

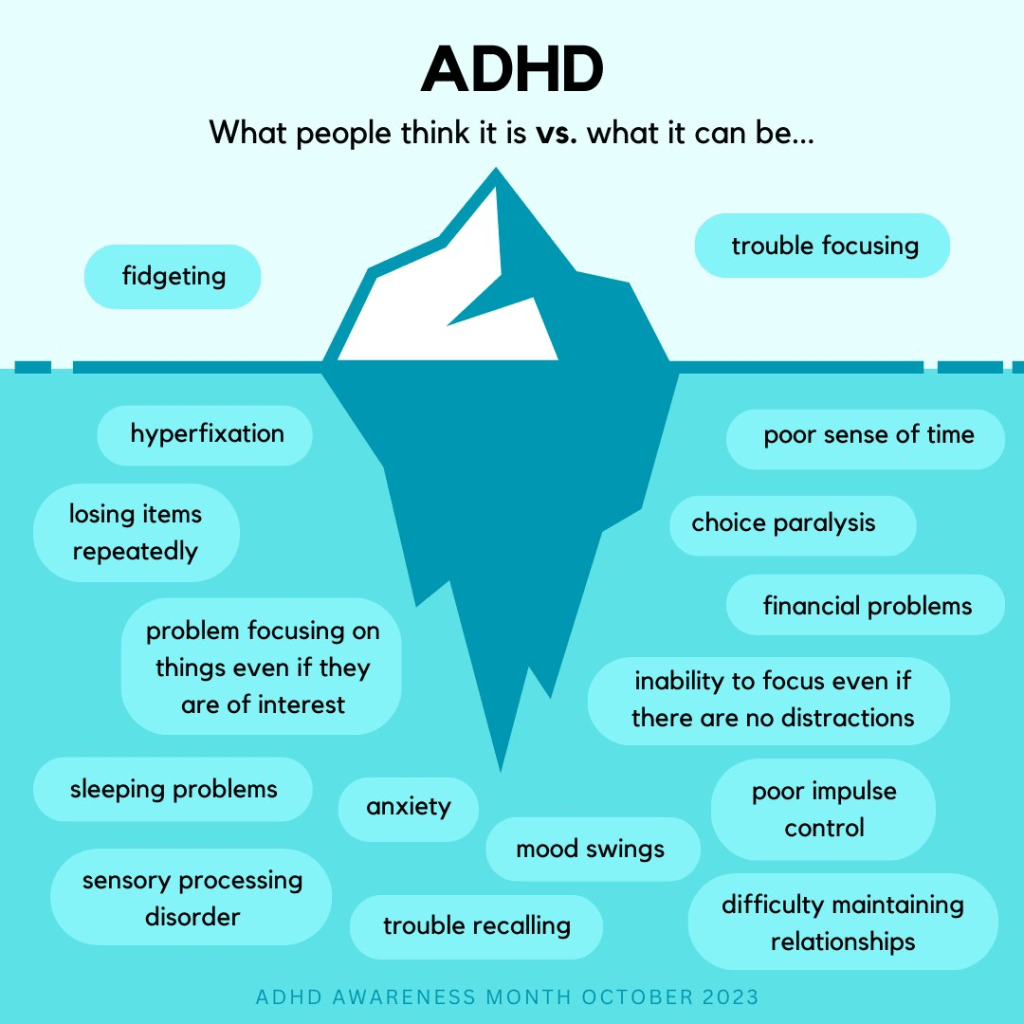

What I’ve learned instead is that ADHD is a boy and girl thing. An adult thing. A wonderful thing and a terribly difficult thing. A perimenopausal thing. A quiet thing and a loud thing. A focused thing and a distracted thing. An anxiety-and-depression thing. A burnout, overwhelm, overstimulation thing. A why does my brain feel like a racetrack at 2 a.m. thing. An emotional train-wreck thing. An I don’t know how to answer questions thing. I can’t organize abstract pieces thing.

What I’ve learned since accepting the reality that I likely have ADHD is that it is vast and deeply unique to each individual. But regardless, it is a very real part of how my brain thinks and functions. It has hundreds of symptoms—some common, some nearly impossible to put into words.

I’ve learned so much about ADHD over the last few years that I can’t imagine knowing myself without this understanding. It explains so much of what I do and who I am—how I think, how I feel, and why I behave the way I do at times. Behavior that can be frustrating or even offensive to others, and often to myself.

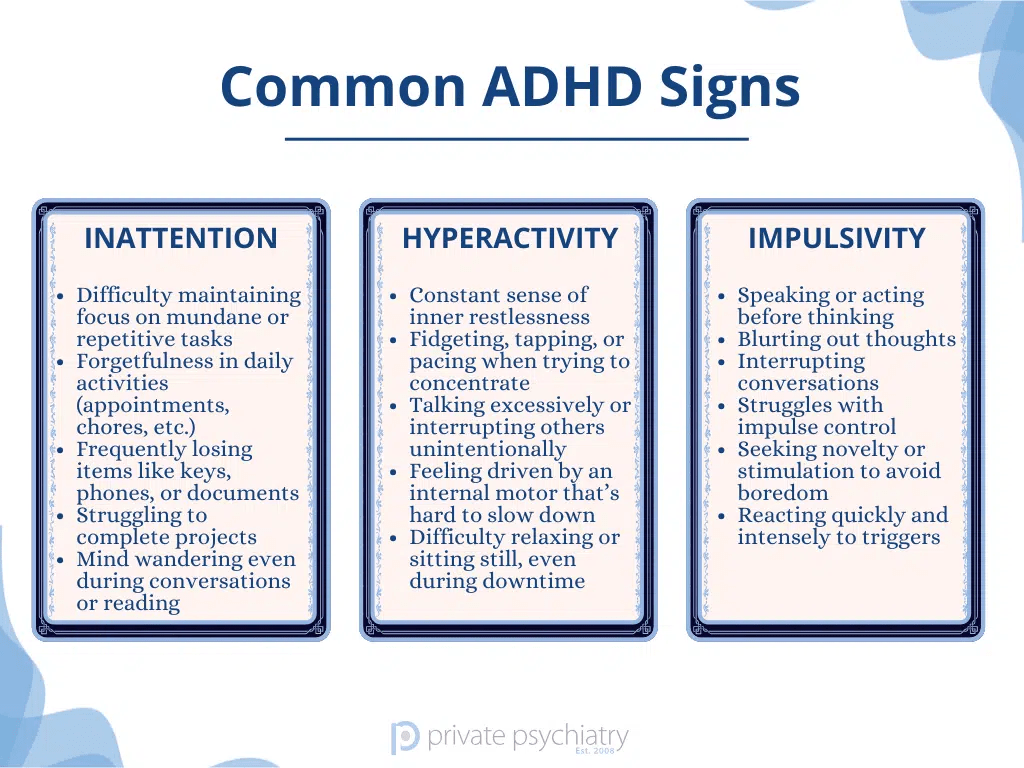

Anyone can Google the symptoms of ADHD. But here’s a place to begin:

ADHD is a mental health disorder and a form of neurodivergent thinking—essentially a way of saying some people’s brains work differently. ADHD affects executive functioning, which is the brain’s management system. This system organizes information into usable actions and helps run day-to-day life.

Executive functioning is responsible for starting tasks (even when you don’t feel like it), staying focused when something isn’t interesting, planning and organizing, managing time, remembering what you’re supposed to be doing, controlling impulses and emotions, prioritizing tasks, and following through to completion.

In an ADHD brain, these processes don’t work as smoothly—as if the management system is impaired. Tasks that feel easy and effortless for a neurotypical brain can become stressful, difficult, and overwhelming for someone with ADHD.

When the brain’s management system struggles, the brain adapts. That’s not because the ADHD brain is broken—but because the human brain is remarkable. It improvises.

I believe the ADHD brain learns to improvise in order to survive, developing creative workarounds and alternative strategies—like a three-legged dog that learns to run in its own way. This adaptability is what makes the ADHD brain not only resilient, but beautiful and valuable to society.

Some even argue that this way of thinking can be uniquely powerful. Many influential and creative figures throughout history are believed to have been neurodivergent in some way, using unconventional minds to reshape the world—people like Einstein, Michelangelo, Van Gogh, Emily Dickinson, Benjamin Franklin, George Orwell, and, more recently, figures such as Bill Gates and Elon Musk. Their brilliance often came not despite their differences, but because of them.

What causes ADHD—nature, nurture, or both—is still debated, though research strongly suggests a combination, with genetics playing a major role. What is generally agreed upon is that ADHD doesn’t simply go away. It’s a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition. If you have it as an adult, you likely had it as a child, even if it wasn’t recognized at the time.

That said, ADHD does change over time, just as the brain changes. As we grow, learn, and adapt, we learn how to grow with it. As children, we’re often forced into rigid molds. As adults, we gain more power to shape our environments and choose paths that suit how our brains work.

You can carve out a life that accommodates your “three legs”—one that highlights strengths rather than constantly punishing weaknesses. That’s why many people with this neurodivergence gravitate toward creative, entrepreneurial, or visionary roles. They build lives that work with their neurodivergence instead of against it.

We learn to cope—often instinctively, often without even realizing we have ADHD. No one teaches you to doodle during a phone call or in a lecture hall. No one teaches a child to hum to drown out background noise. These are adaptations, learned quietly and early.

That’s part of why I’m hesitant about medicating children before their brains are fully developed and before they’ve had the chance to discover their own coping mechanisms. I believe we can train our brains, build supportive habits, and learn “tricks of the trade”—not to erase ADHD, but to harness it so it doesn’t run our lives.

Because life is harder with ADHD. Everything takes more effort—everything except creativity.

It’s harder to be on time.

Harder to stay on task.

Harder to focus long enough to finish.

Harder to read instructions, follow directions, make decisions, manage stress, and navigate people.

Social interaction can be exhausting.

Masking is common

Change is difficult. There’s a powerful need for sameness.

Novelty can create anxiety.

Unfamiliarity can be disorienting.

burn out is almost unavoidable.

These are just some basics of ADHD. Its not exhaustive, but it’s a start.