The other night we visited a Catholic shrine decorated with Christmas lights, where people stroll and sip hot cocoa. At the center of the path stood a hill with a large cross, and beneath it a small cave holding a nativity scene.

“Let’s go see baby Jesus,” I said to my husband.

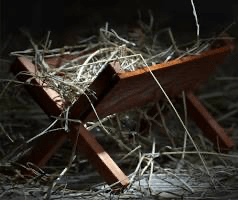

Mary knelt. Joseph leaned on his staff. Shepherds gazed downward. But the manger was empty.

A little boy beside us cried out, “Where’s the baby?”

Jesus was missing.

I found it oddly humorous—not only because I’m not Catholic and place little value on resin statues, but because of the question itself: who would steal baby Jesus, and why? Yet the image lingered. A missing Jesus. It struck me as a familiar story, one repeated throughout history—and in individual hearts.

I am doing the best I can. Life feels relentless. I am exhausted, angry, overwhelmed. I wake tired and discouraged, burdened by stress and disappointment. I want someone to see me, to kneel beside me, to show compassion and help me.

“Where is God?” I ask. “Where are you, Lord? Isn’t Jesus supposed to save?”

That is the promise of Christmas, after all: a Savior who sees us, who understands weakness, who is near. But I don’t feel saved. I feel lost—surrounded by uncertainty, walking a hard road, hearing voices that tell me I am alone.

Scripture tells us even Mary lost Jesus.

When he was twelve, Mary and Joseph traveled home from Jerusalem and only after days realized he was missing. They had assumed he was with them. Worn out by travel, distracted by responsibility, they lost sight of the Messiah.

Mary’s life was marked by movement—journeys to Elizabeth, to Bethlehem, to Egypt, back again, always traveling. I wonder how she felt when she realized Jesus was gone. Angry? Afraid? Overwhelmed? Did she feel accused or abandoned? She does speak with sharpness when she finds him: “Why have you treated us this way?”

We rarely allow Mary such human emotion, yet perhaps she too asked, “Where is God?”

I confess—I smiled when I realized this. Even Mary lost Jesus.

Caught in crowds and chaos, she journeyed on without him. And when she found him, she did not find the boy she left behind. She found a teacher, a rabbi, the Son of God—standing in his Father’s house. She left him her son; she found him her Savior.

This loss was necessary. It shifted her vision. She could never again see Jesus merely as her child.

That speaks to me.

I have loved Jesus, walked with him, held him close—and now he feels gone. We are told God never leaves us, yet Scripture tells a more complex story. God left Noah in the ark, Abraham in waiting, Moses in the wilderness. Jesus left his mother, and later his disciples. Why would we be exempt from seasons of absence?

Perhaps this leaving is part of faith. Christ first comes to us gently, like a child we keep close. And then, for a time, he withdraws—so that we must search for him as he once searched for us.

Especially in Advent, when Jesus is endlessly returned to the manger—small, helpless, safe—I wonder if we are meant to notice what is missing. He is no longer a baby. He is not even merely the man on the cross. We must go back to the Father’s house to find him anew: the Bridegroom, the Word made flesh, the Lion of Judah, the King of Kings.

We all lose Jesus at times—even the most devoted. And thank God we do. Because when we go back and search, we do not find the Jesus we once knew, but the Jesus we have not yet known.